Hello World

Let's write and deploy our first smart contract!

https://play.onflow.org/f51905e8-6030-4641-9324-11a3f1a6091c

The tutorial will ask you to take various actions to interact with this code.

A smart contract is a program that verifies and executes the performance of a contract without the need for a trusted third party. Programs that run on blockchains are commonly referred to as smart contracts because they mediate important functionality (such as currency) without having to rely on a central authority (like a bank).

Before you get started with Flow, you need to understand how accounts and transactions are modeled on Flow and in Cadence.

Accounts and Transactions

Like most other blockchains, the programming model in Flow is centered around accounts and transactions. All state that persists permanentely is stored in accounts and there is only one type of account (all accounts can be for any number of users, smart contracts, and data).

The interfaces to this state (the ways to interact with it) are also stored in accounts. All code execution takes place within transactions, which are blocks of code that are authorized and submitted by external users to interact with the persistent state, which includes directly modifying account storage.

What is an account?

Each user has an account controlled by one or more private keys with configurable weight. This means that support for accounts/wallets with multiple controllers is built into the protocol by default.

An account is divided into two main areas:

The first area is the contract area. This is the area that stores any number smart contracts that contain type definitions, fields, and functions that relate to a common functionality. This area also holds contract interfaces, which are basically program guidelines that other contracts can import and implement. This area cannot be directly accessed in a transaction unless the transaction is just returning (aka reading) a copy of the code deployed to an account. The owner of an account can directly add, remove, or update/overwrite contracts that are stored in it.

The second area is the account storage. This area is where an account stores the objects that they own and the capabilities for controlling how these objects can be accessed.

Account Storage

The account storage functions similar to a traditional filesystem; Data is stored in paths. A link can be created from one path (source) to another (target) to change different permissions and functionality of the object in the target path. and only the owner of the account has "root" access to modify any of the data or links.

Objects, which can be as simple as an integer to as complex as a struct or resource(an important type that we'll discuss later!),

are stored under paths in the account filesystem. Paths consist of a domain and an identifier.

Paths start with the character /, followed by the domain, the path separator /, and finally the identifier.

For example, the path /storage/test has the domain storage and the identifier test.

There are only three valid domains which represent the three areas in the account storage: storage, private, and public.

Identifiers are custom and can be any name you want them to be to indicate what is stored in that path. It is recommended you make your identifiers very specific so that there is a smaller chance of them conflicting with other projects' identifiers.

Account Filesystem Domain Structure (Where can I store my stuff?)

- The

storagedomain is where all objects (such as structs and resource objects representing tokens or NFTs) are stored. It is only directly accessible by the owner of the account. - The

privatedomain is like a private API. You can optionally create links to any of your stored assets here. Only the owner and anyone they give access to can use these interfaces to call functions that are defined in their stored assets. - The

publicdomain is your account's public API. It is like theprivatedomain in that the owner can link capabilities here that point to stored assets. The difference is that anyone in the network can access thepublicdomain's functionality.

A Transaction in Flow is defined as an arbitrary-sized block of Cadence code

that is signed by one or more accounts.

Transactions have access to the /storage/ and /private/ domains of the accounts

that signed the transaction.

Transactions can also read and call functions in public contracts, and access public domains in other users' accounts.

Creating a Smart Contract

We will start by writing a smart contract that contains a public function that returns "Hello World!".

First, you'll need to follow this link to open a playground session with the Hello World contracts, transactions, and scripts pre-loaded:

https://play.onflow.org/f51905e8-6030-4641-9324-11a3f1a6091cOpen the Account 0x01 tab with the file called

HelloWorld.cdc.

HelloWorld.cdc should contain this code:

pub contract HelloWorld {

// Declare a public field of type String.

//

// All fields must be initialized in the init() function.

pub let greeting: String

// The init() function is required if the contract contains any fields.

init() {

self.greeting = "Hello, World!"

}

// Public function that returns our friendly greeting!

pub fun hello(): String {

return self.greeting

}

}

A contract is a collection of code (its functions) and data (its state) that lives in the contract area of an account in Flow. Accounts can have one or more contracts and/or contract interfaces, and these can be freely added, removed, or updated (with some restrictions) by the owner of the account.

The line pub let greeting: String declares a public (pub) state constant (let) called greeting of type String.

We would have used var if we wanted to declare a variable, meaning that the value can be changed later instead of being constant like with let.

The pub keyword is an example of an access control specification meaning that it can be accessed in all scopes, but not written to in all scopes.

You can also use access(all) interchangeably with pub if you prefer something more descriptive.

Please refer to the Access Control section of the language reference

to learn more about the different levels of access control permitted in Cadence.

The init() section is called the initializer. It is a special function that is only run when the contract is created and never again.

Objects similar to contracts, such as other composite types like structs or resources,

require that the init() function initialize any fields that are declared in a composite type.

In this example, the initializer sets the greeting field to "Hello, World!".

Next is a public function declaration that returns a value of type String.

Anyone who imports this contract in their transaction or script can read the public fields,

use the public types, and call the public contract functions; i.e. the ones that have pub or access(all) specified.

Now we can deploy this contract to your account and run a transaction that calls its function.

Deploying Code

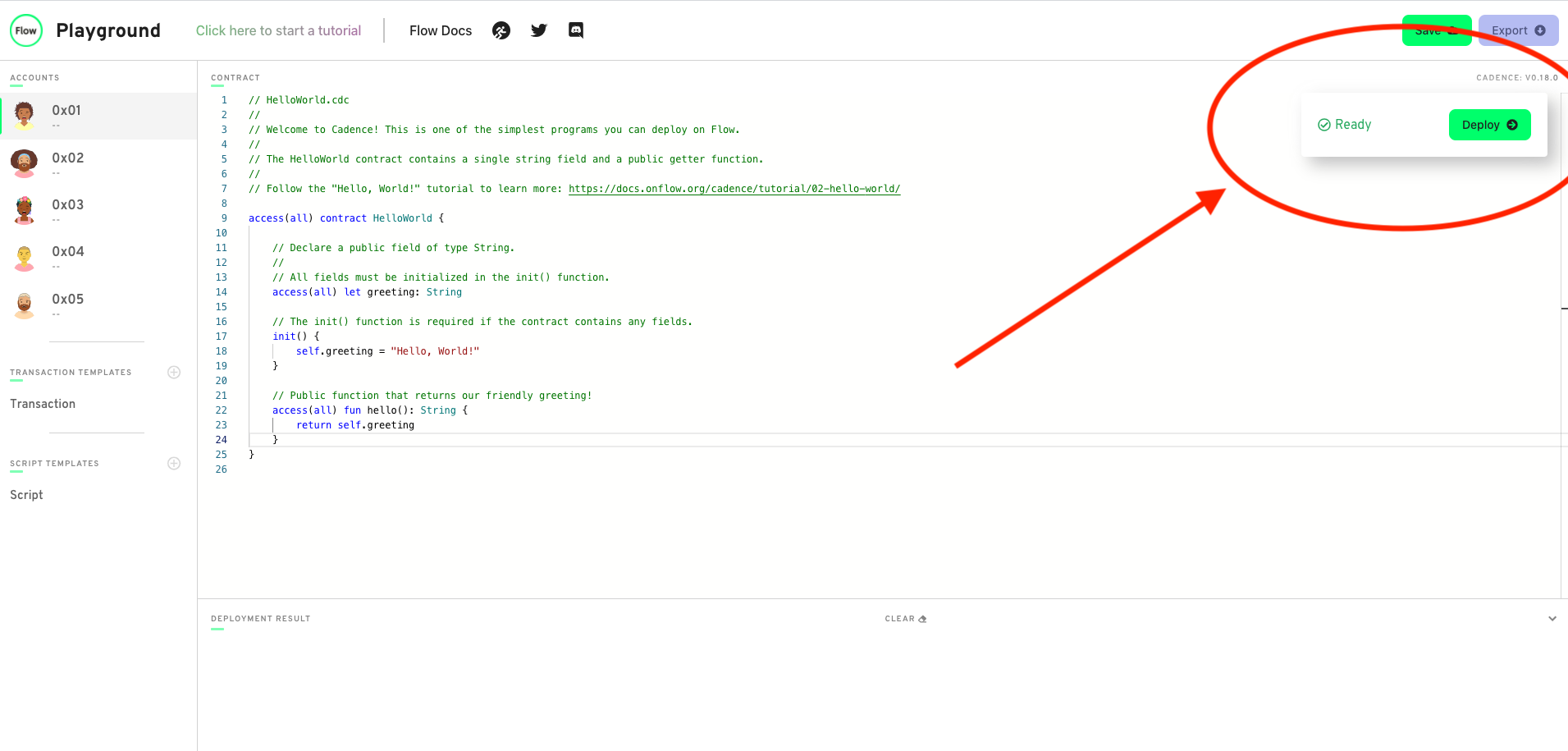

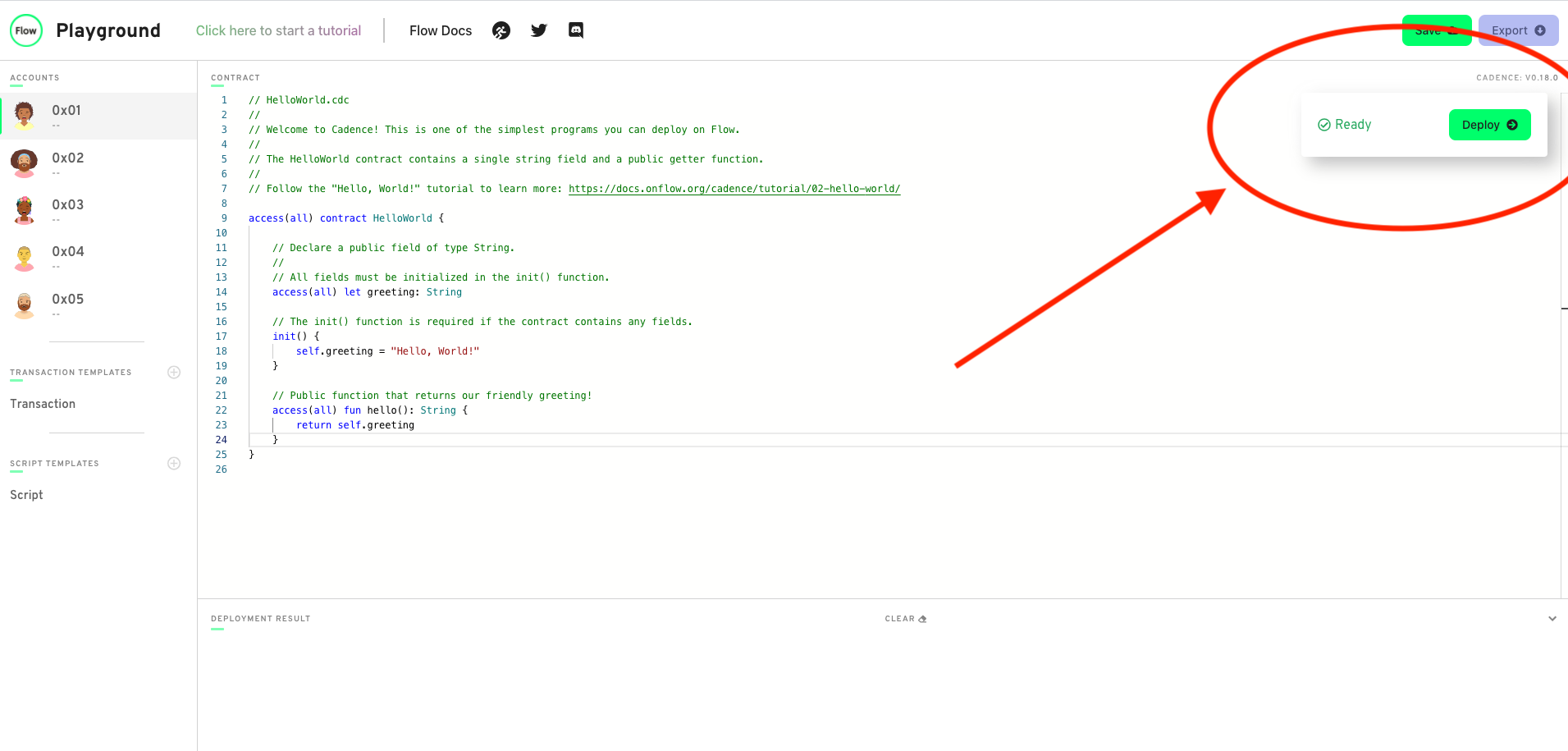

Now that you have some Cadence code to work with, you can deploy it to your account.

Make sure that the account 0x01 tab is selected and that the

HelloWorld.cdc file is in the editor.

Click the deploy button to deploy the contents of the editor to account 0x01.

You should see a log in the output area indicating that the deployment succeeded.

Deployed Contract To: 0x01

You'll also see the name of the contract show up in the selected account tab underneath the number for the account.

This indicates that the HelloWorld contract has been deployed to the account.

You can always look at this tab to verify which contracts are in which accounts,

but there can only be one contract per account in the Flow Playground.

Creating a Transaction

Open the transaction named Say Hello

Say Hello should contain this code:

import HelloWorld from 0x01

transaction {

// No need to do anything in prepare because we are not working with

// account storage.

prepare(acct: AuthAccount) {}

// In execute, we simply call the hello function

// of the HelloWorld contract and log the returned String.

execute {

log(HelloWorld.hello())

}

}

This is a Cadence transaction. A transaction can contain arbitrary code that imports from other accounts, interacts with account storage, interacts with other accounts, and more.

To interact with a smart contract, the transaction first needs to import that smart contract by retrieving its definition from the address where it is stored. This imports the interface definitions, resource definitions, and public functions from that contract so that the transaction can use them to interact with the contract itself or with other accounts that utilize that contract.

To import a smart contract from another account, you type this line at the top of your transaction:

import {ContractName} from {Address}

Now, all of the public fields, types, and functions defined by that contract

are available within your transaction by using the ContractName.member syntax.

Transaction Structure

Transactions are divided into two main phases, prepare and execute.

- The

preparephase is required, but is not used here. We'll cover this phase later on. - The

executephase is the main body of a transaction. It can call functions on external contracts and objects and perform operations on data that was initialized in the transaction.

In this transaction, we are importing the contract from the address that it was deployed to and calling its hello function.

In the box at the top right of the editor, select Account 0x01 as the

transaction signer.

Click the Send button to submit the transaction

You should see something like this:

"Hello, World!"

Congratulations, you just executed your first Cadence transaction! :100:

Creating a Resource

Next, we are going to get some practice with an example that uses resources, one of the defining features in Cadence. A resource is a composite type like a struct or a class, but with some special rules.

Open the Account 0x02 tab with file named HelloWorldResource.cdc.

HelloWorldResource.cdc should contain the following code:

pub contract HelloWorld {

// Declare a resource that only includes one function.

pub resource HelloAsset {

// A transaction can call this function to get the "Hello, World!"

// message from the resource.

pub fun hello(): String {

return "Hello, World!"

}

}

init() {

// Use the create built-in function to create a new instance

// of the HelloAsset resource

let newHello <- create HelloAsset()

// We can do anything in the init function, including accessing

// the storage of the account that this contract is deployed to.

//

// Here we are storing the newly created HelloAsset resource

// in the private account storage

// by specifying a custom path to the resource

// Make sure the path is specific to avoid path collision!

self.account.save(<-newHello, to: /storage/HelloAssetTutorial)

log("HelloAsset created and stored")

}

}

Deploy this code to account 0x02 using the Deploy button.

This is another example of what we can do with a contract. Cadence can declare type definitions within deployed contracts. A type definition is simply a description of how a particular set of data is organized. It isn't a copy of that data on its own. Any account can import these definitions and use them to create an object that follows that definition or to interact with other objects of those types.

This contract that we just deployed declares a definition for the HelloAsset resource.

Let's walk through this contract, starting with the resource. Resources are one of the most important things that Cadence introduces to the smart contract design experience:

pub resource HelloAsset {

pub fun hello(): String {

return "Hello, World!"

}

}

Resources are a composite type similar to a struct or a class because they can have any number of fields or functions within them. The difference is how code is allowed to interact with them.

- Each instance of a resource can only exist in exactly one location and cannot be copied. Here, location refers to account storage, a temporary variable in a function, a storage field in a contract, etc.

- Resources must be explicitly moved from one location to another when accessed.

- Resources also cannot go out of scope at the end of a function execution. They must be explicitly stored somewhere or destroyed.

These characteristics make it impossible to accidentally lose a resource from a coding mistake.

Resources are useful when you want to model direct ownership. Traditional structs or classes from other conventional programming languages are not an ideal way to represent ownership because they can be copied. This means a coding error can easily result in creating multiple copies of the same asset, which breaks the scarcity requirements needed for these assets to have real value. We have to consider loss and theft at the scale of a house, a car, or a bank account with millions of dollars, or a horse. Resources, in turn, solve this problem by making creation, destruction, and movement of assets explicit.

init() {

// ...

This example also declares an init() function. All composite types like contracts, resources, and structs can have an optional init() function

that only runs when the object is initially created. Cadence requires that all fields must be explicitly initialized,

so if the object has any fields, this function has to be used to initialize them.

Contracts also have read and write access to the storage of the account that they are deployed to

by using the built-in self.account object.

This is an AuthAccount object

that gives them access to many different functions to interact with the private storage of the account.

In this contract's init function, the contract uses the create keyword

to create an instance of the HelloAsset type and saves it to a local variable.

To create a new resource object, we use the create keyword

followed by an invocation of the name of the resource with any init() arguments.

A resource can only be created in the scope that it is defined in.

This prevents anyone from being able to create arbitrary amounts of resource objects that others have defined.

The Move Operator (<-)

let newHello <- create HelloAsset()

Here we use the <- symbol. This is the move operator.

The move operator <- replaces the assignment operator = in assignments that involve resources.

To make assignment of resources explicit, the move operator <- must be used when:

- the resource is the initial value of a constant or variable,

- the resource is moved to a different variable in an assignment,

- the resource is moved to a function as an argument

- the resource is returned from a function.

When a resource is moved, the old location is invalidated, and the object moves into the context of the new location.

So if I have a resource in first_resource, like so:

// Note the `@` symbol to specify that it is a resource

let first_resource: @AnyResource = create AnyResource()

and I want to assign it to a new variable, second_resource,

after I do the assignment, first_resource is invalid because the underlying resource has been moved to the new variable.

var second_resource <- first_resource

// first_resource is now invalid. Nothing can be done with it

Regular assignments of resources are not allowed because assignments only copy the value. Resources can only exist in one location at a time, so movement must be explicitly shown in the code.

Back to our init function, after creating the HelloAsset resource,

it uses the AuthAccount.save function to store the resource in the account storage.

self.account.save(<-newHello, to: /storage/HelloAssetTutorial)

A contract can refer to its member functions and fields with the keyword self.

All contracts have access to the storage of the account where they are deployed and can access that AuthAccount object with self.account.

AuthAccount objects have many different methods that are used to interact with account storage.

You can see the documentation for all of these in the account section of the language reference.

The save method saves an object to account storage. The type parameter for the object type

is contained in <> to indicate what type the stored object is.

It can also be inferred from the argument's type, but it is often safe to be explicit anyway.

The first parameter to save is the object that is being stored, and the to parameter is the path that the object is being stored at.

The path must be a storage path, i.e., only the domain /storage/ is allowed as the to parameter.

If there is already an object stored under the given path, the program aborts. Remember, the Cadence type system ensures that a resource can never be accidentally lost. When moving a resource to a field, into an array, into a dictionary, or into storage, there is the possibility that the location already contains a resource. Cadence forces the developer to handle the case of an existing resource so that it is not accidentally lost through an overwrite.

It is also very important when choosing the name of your paths to pick an identifier that is very specific and unique to your project. Currently, account storage paths are global, so there is a chance that projects could use the same storage paths, which could cause path conflicts! This could be a headache for you, so choose unique path names to avoid this problem.

Try removing the line of code that saves newHello to storage.

You should see an error for newHello that says loss of resource.

This means that you are not handling the resource properly.

If you ever see this error in any of your programs, it means there is a resource somewhere

that is not being explicitly stored or destroyed, meaning the program is invalid.

Add the line back to make the contract check properly.

In this case, this is the first transaction we have run with the selected account,

so we know that the storage spot at /storage/HelloAssetTutorial is empty.

In real applications, we would likely perform necessary checks and actions with the location we are storing to

to make sure we don't abort the transaction because of an accidental overwrite.

Now that you have deployed the contract, account 0x02 should have the newly created HelloWorld.HelloAsset

resource stored in its storage. Lets check to make sure this is true with a transaction.

Interacting with a Resource

Open the transaction named Load Hello.

Load Hello should contain the following code:

import HelloWorld from 0x02

// This transaction calls the "hello" method on the HelloAsset object

// that is stored in the account's storage by removing that object

// from storage, calling the method, and then putting it back in storage

transaction {

prepare(acct: AuthAccount) {

// load the resource from storage, specifying the type to load it as

// and the path where it is stored

let helloResource <- acct.load<@HelloWorld.HelloAsset>(from: /storage/HelloAssetTutorial)

// We use optional chaining (?) because the value in storage

// may or may not exist, and thus is considered optional.

log(helloResource?.hello())

// Put the resource back in storage at the same spot

// We use the force-unwrap operator `!` to get the value

// out of the optional. It aborts if the optional is nil

acct.save(<-helloResource!, to: /storage/HelloAssetTutorial)

}

}

This transaction imports the HelloWorld definitions from the account we just deployed them to, removes the HelloAsset object from storage,

and calls the hello() function of the stored HelloAsset resource.

This transaction also is our first to use the prepare phase!

The prepare phase is the only place that has access to the signing accounts' private AuthAccount object.

AuthAccount has special methods that allow saving to and loading from /storage/,

and creating /private/ and /public/ links to the objects in /storage/,

called capabilities (more on these later).

The execute phase does not have access to AuthAccount and thus can only use objects

that were removed from the AuthAccount in the prepare phase or created in the prepare phase.

By not allowing the execute phase to access account storage, we can statically verify which assets and areas of the signers storage a given transaction can modify. Browser wallets and applications that submit transactions for users can use this to show what a transaction could alter, giving users information about transactions that wallets will be executing for them, and confidence that they aren't getting fed a malicious or dangerous transaction from an app or wallet.

You can have multiple signers of a transaction by clicking multiple account avatars in the playground, but the number of parameters of the prepare block of the transaction NEEDS to be the same as the number of signers. If not, this will cause an error.

To remove an object from storage, we use the load method.

let helloResource <- acct.load<@HelloWorld.HelloAsset>(from: /storage/HelloAssetTutorial)

If no object of the specified type is stored under the given path, the function returns nil. (This is an Optional,

a special type of data that we will cover later)

If there is an object of the specified type at the path, the function returns that object and the storage will longer contain an object under the given path.

The type parameter for the object type to load is contained in <>.

A type argument for the parameter must be provided explicitly, which is @HelloWorld.HelloAsset here.

(Note the @ symbol to specify that it is a resource)

The path from must be a storage path, i.e., only the domain /storage/ is allowed.

Next, we call the hello function and log the output.

log(helloResource?.hello())

We use ? because the values in the storage are returned as optionals.

Optionals are values that can represent the absence of a value.

Optionals have two cases: either there is a value of the specified type, or there is nothing (nil).

An optional type is declared using the ? suffix.

let newResource: HelloAsset? // could either have a value of type `HelloAsset`

// or it could have a value of `nil`

Optionals allow developers to account for nil cases more gracefully.

Here, we explicitly have to account for the possibility that the helloResource object we got with load is nil

(because load will return nil if there is nothing there to load).

Using ? "unwraps" the optional, meaning that it gets the value if it is there, before calling hello,

but only if the value isn't nil. If the value is nil, the ? returns nil.

Because ? is used when calling the hello function, the function call only happens if the stored value is not nil.

In this case, the result of the hello function will be returned as an optional.

However, if the stored value was nil, the function call would not occur and the result is nil.

Next, we use save again to put the object back in storage in the same spot:

acct.save(<-helloResource!, to: /storage/HelloAssetTutorial)

Remember, helloResource is still an optional, so we have to handle the possibility that it is nil.

Here, we use the force-unwrap operator (!). This operator gets the value in the optional if it contains a value,

and aborts the entire transaction if the object is nil.

It is a more risky way of dealing with optionals, but if your program is ever in a state where a value being nil

would defeat the purpose of the whole transaction, then the force-unwrap operator might be a good choice to deal with that.

Refer to Optionals In Cadence to learn more about optionals and how they are used.

Select account 0x02 as the only signer. Click the Send button to submit

the transaction.

You should see something like this:

"Hello, World!"

Creating Capabilities and References to Stored Resources

In this example, we create a link and reference to your HelloAsset resource object, then use that reference to call the hello function.

A detailed explanation of what is happening in this transaction is below the transaction code so, if you feel lost, keep reading!

Open the transaction named Create Link.

Create Link should contain the following code:

import HelloWorld from 0x02

// This transaction creates a new capability

// for the HelloAsset resource in storage

// and adds it to the account's public area.

//

// Other accounts and scripts can use this capability

// to create a reference to the private object to be able to

// access its fields and call its methods.

transaction {

prepare(account: AuthAccount) {

// Create a public capability by linking the capability to

// a `target` object in account storage.

// The capability allows access to the object through an

// interface defined by the owner.

// This does not check if the link is valid or if the target exists.

// It just creates the capability.

// The capability is created and stored at /public/Hello, and is

// also returned from the function.

let capability = account.link<&HelloWorld.HelloAsset>(/public/HelloAssetTutorial, target: /storage/HelloAssetTutorial)

// Use the capability's borrow method to create a new reference

// to the object that the capability links to

// We use optional chaining "??" to get the value because

// result of the borrow could fail, so it is an optional.

// If the optional is nil,

// the panic will happen with a descriptive error message

let helloReference = capability.borrow()

?? panic("Could not borrow a reference to the hello capability")

// Call the hello function using the reference

// to the HelloAsset resource.

//

log(helloReference.hello())

}

}

Ensure account 0x02 is still selected as a transaction signer.

Click the Send button to send the transaction.

You should see "Hello, World" show up in the console again.

You might be confused that we were able to call a method on the HelloAsset object

without actually being directly in control of it!

It is also stored in the /storage/ domain of the account, which should be private.

This is because we created a capability for the HelloAsset object.

Capabilities are kind of like pointers in other languages.

Capability Based Access Control

Capabilities allow the owners of objects to specify what functionality of their private objects is available to others. Think of it kind of like an account's public API, if you're familiar with the concept. The account owner has private objects stored in their storage, like their collectibles or their money, but they might still want others to be able to see what collectibles they have in their account, or they want to allow anyone to deposit more money of a certain currency in their account. Since these objects are stored in private storage by default, the owner has to do something to open up access to these while still retaining full control. We create capabilities to accomplish this.

In our example, the owner of HelloAsset might still want to let other people call the hello method.

This is what capabilities are for. They represent a link to an object in an account's storage that has the type specified when the link is created.

It is important to remember that someone else who has this capability cannot move or destroy

the object that the capability is linked to! They can only access fields

that the owner has explicitly declared in the type specification of the link method (described below).

Capabilities do not have any meaningful functionality on their own, but every capability has a borrow method,

which creates a reference to the object that the capability is linked to.

This reference is used to read fields or call methods on the object they reference as if the owner of the reference had the actual object.

Note that this only allows access to field and methods. It does not allow coping, moving, or modifying the original object directly.

This Transaction, step-by-step

Let's break down what is happening in this transaction.

First, we create a capability that is linked to the private HelloAsset object in /storage/:

let capability = account.link<&HelloWorld.HelloAsset>(/public/Hello, target: /storage/Hello)

The HelloAsset object is stored in /storage/HelloAssetTutorial, which only the account owner can access.

They want any user in the network to be able to call the hello method. So they make a public capability in /public/HelloAssetTutorial.

To create a capability, we use the AuthAccount.link method to link a new capability to an object in storage.

The type contained in <> is the restricted reference type that the capability represents.

The capability says that whoever borrows a reference from this capability can only have access to the fields and methods

that are specified by the type in <>.

The specified type has to be a subtype of the type of the object being linked to,

meaning that it cannot contain any fields or functions that the linked object doesn't have.

A reference is referred to by the & symbol. Here, the capability references the HelloAsset object,

so we specify <&HelloWorld.HelloAsset> as the type, which give access to everything in the HelloAsset object.

The first argument to the link function is the path where you want to store the link for the capability

and the target argument is the path to the object in storage that is to be linked to.

We always store links for capabilities in the /private/ or /public/ domains:

- We choose

/private/if we only want to allow one or a small number of users to access it - We choose

/public/if we want any user in the network to be able to access it. Capabilities always link to objects in the/storage/domain.

To borrow a reference to an object from the capability, we use the capability's borrow method.

let helloReference = capability.borrow()

?? panic("Could not borrow a reference to the hello capability")

This method creates the reference as the type we specified in <> in the link function.

While borrowing the reference, we use optional chaining

because the borrowing of the reference could fail.

The reference could be nil if the targeted storage slot is empty, is already borrowed, or if the requested type exceeds what is allowed by the capability.

We panic with a descriptive error message so the caller can know better what went wrong.

The reason we separate this process into capabilities and references is to protect against re-entrancy bugs where a malicious actor could call into an object multiple times. These bugs have plagued other smart contract languages. Only one reference to an object can exist at a time, so this type of vulnerability isn't possible for objects in storage.

Additionally, the owner of an object can effectively revoke capabilities they have created

by moving the underlying object or destroying the link with the unlink method.

If the referenced object is moved or the link is destroyed, capabilities that have been created from that link are invalidated.

You can find more detailed documentation about capabilities in the language reference.

Now, anyone can call the hello() method on your HelloAsset object by borrowing a reference with your public capability in /public/Hello!

(Covered in the next section)

Lastly, we call the hello() method with our borrowed reference:

// Call the hello function using the reference to the HelloAsset resource

log(helloReference.hello())

At the end of the transaction execution, the helloReference value is lost,

but that is ok because while it references a resource, it isn't the actual resource itself, so it is ok to lose it.

Executing Scripts

A script is a very simple transaction type in Cadence that cannot perform any writes to the blockchain and can only read the state of an account. It runs without permissions from any account.

To execute a script, you write a function called pub fun main(). You can click the execute script button to run the script.

The result of the script will be printed to the console output.

Open the file Script1.cdc.

Script1.cdc should look like the following:

import HelloWorld from 0x02

pub fun main() {

// Cadence code can get an account's public account object

// by using the getAccount() built-in function.

let helloAccount = getAccount(0x02)

// Get the public capability from the public path of the owner's account

let helloCapability = helloAccount.getCapability<&HelloWorld.HelloAsset>(/public/HelloAssetTutorial)

// borrow a reference for the capability

let helloReference = helloCapability.borrow()

?? panic("Could not borrow a reference to the hello capability")

// The log built-in function logs its argument to stdout.

//

// Here we are using optional chaining to call the "hello"

// method on the HelloAsset resource that is referenced

// in the published area of the account.

log(helloReference.hello())

}

This script fetches the PublicAccount object with getAccount.

let helloAccount = getAccount(0x02)

The PublicAccount object is available to anyone in the network for every account,

but only has access to a small subset of functions that can only read from the /public/ domain in an account.

See more about accounts here: https://docs.onflow.org/cadence/language/accounts/

Then, it gets the capability that was created in Create Link.

// Get the public capability from the public path of the owner's account

let helloCapability = helloAccount.getCapability(/public/HelloAssetTutorial)

To get a capability that is stored in an account, we use the account.getCapability function.

This function is available on AuthAccounts and on PublicAccounts.

It returns a capability for the link at the path that is specified,

also with the type that is specified. It does not check if the target exists,

so the borrow will fail if the capability is invalid.

After that, the script borrows a reference from the capability.

let helloReference = helloCapability.borrow()

Then, the script uses the reference to call the hello function and prints the result.

Lets execute the script to see it run correctly.

Click the Execute button in the playground.

You should see something like this print:

> "Hello, World"

> Result > "void"

Good work! You've deployed your first Cadence smart contracts and used transactions and scripts to interact with them!

Now that you have written and launched your first smart contract on Flow, you're ready for something more complex! The Fungible Token tutorial will teach you how to build a simple token on Flow. Also, it is highly recommended to check out the Cadence Best Practices document and Anti-patterns document before doing any real development.

Here are a few pointers on certain aspects of the Playground if you still need some clarification.

Accounts

The playground is initialized with a configurable number of default accounts when you open it.

In the playground, you can select accounts to edit the contracts that are deployed for them by selecting the tab for that account in the left section of the screen. The contract corresponding to that account will be displayed in the editor where you can edit and deploy it to the blockchain.

Upgrading contracts that are already deployed is very risky, so be careful!

Transactions

Once a contract has been deployed, you can submit transactions to interact with it. In the transactions selection section on the left side of the screen, you can select different transactions to edit and send. While a transaction is open, you can select one or more accounts to sign a transaction. This is because in Flow, multiple accounts can sign the same transaction, giving the access to their private storage. If multiple accounts are selected as signers, this needs to be reflected in the signature of the transaction to show multiple signers:

// One signer

transaction {

prepare(acct1: AuthAccount) {}

}

// Two signers

transaction {

prepare(acct1: AuthAccount, acct2: AuthAccount) {}

}

If you want more practice, you can run some of the previous transactions on new accounts to explore some different interactions and potential error messages.